Avtar Mota

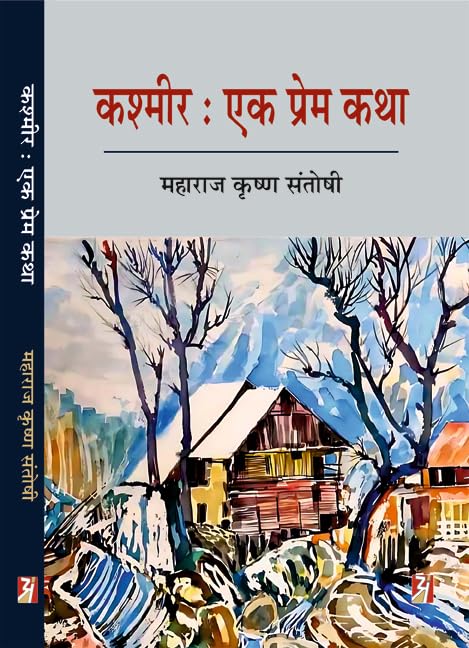

KASHMIR: EK PREM KATHA

(A Collection of Short Stories in Hindi)

by Maharaj Krishen Santoshi

Published by Antika Prakashan, Ghaziabad

Price Rs300/= ( Available on Amazon India )

Year of Publication 2024

Maharaj Krishen Santoshi, a prominent Hindi author currently in exile, hails from Kashmir. He has penned over eight books, ranging from poetry to short stories that reflect his experiences of life in Kashmir—an area he deeply cherishes and mourns. His works are available in translations across multiple languages, including English, Punjabi, Telugu, Gujarati, Kashmiri, and Dogri. Notably, he has received recognition from the Central Hindi Directorate (Government of India), J&K Academy of Art, Culture and Languages, and the UP Hindi Society.

Santoshi demonstrates a mastery akin to that of Anton Chekhov, skillfully articulating the pains of individuals whose experiences are often overshadowed. In the stories presented in this book, he approaches a narrative style reminiscent of Manto’s that unabashedly confronts themes of loss, displacement, and the brutal impacts of violence. Readers will find evocative imagery, a touch of dark humor, and a profound grasp of human psychology woven throughout.

This collection comprises 15 short stories along with diary entries from the author, spanning 96 pages. The stories include titles such as Darashikoh Ki Maut, Pandit Kashi Nath MA (History), Mitti Ki Gawahi, Chinar, Teen Kisse, Kashmir: Eik Prem Katha, Saanp Aur Boodi Aurat, Antaratma, Bhaand Aur Bhagwan, Pahalwan Ki Moonchh, Poshmaal Ka Bageecha, Vrishabh, Jannat Ki Sair, Rinn-mukt, Eik Tha Comrade, and Hum Kahin Bhool Na Jaayein (diary entries of a displaced Kashmiri).

Set against the backdrop of Kashmir, Santoshi’s stories encapsulate nostalgia, human displacement, longing, and the complexities of exile. Readers will perceive a façade of life lived by the characters in Kashmir, palpable in their actions and Santoshi’s expressive storytelling. These narratives provide a glimpse into the historical context of the traumatic displacement experienced by Kashmiri Pandits during the 1990s, following the eruption of terrorism supported by Pakistan.

In “Dara Shikoh Ki Maut,” Santoshi juxtaposes two opposing ideologies—religious bigotry and humanism, represented by Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh. The poignant demise of ‘Kashi Nath MA (History)’ in a Jammu camp post-displacement deeply resonates with readers. Kashi Nath envisioned a serene retirement until terrorism forcibly uprooted him and his family from their homeland. In “Chinar,” a Kashmiri Pandit family attempts to plant a Chinar tree in their new home, yearning to stay connected to their roots. Alas, the tree struggles to flourish and painfully intertwines with the foundation of their new house in Jammu, ultimately needing to be cut down. “Bhaand Aur Bhagwan” explores the unique ritual of Muslim Bhaands performing Puja for their Devi in Kashmir, a tradition threatened by the rising tide of religious extremism fueled by terrorism. “Rinn-mukt” narrates the solitary existence of a Kashmiri Pandit who, having settled his family across various locales, grapples with the disconnection from his roots. Through “Poshmaal Ka Bagicha,” Santoshi illustrates the profound bond Kashmiri Pandits share with Jaffur or marigold flowers, essential in their daily Pujas and other ceremonies. Poshmaal, a Kashmiri Pandit female character, cultivates these blossoms in her tent in Jammu, passing away while gazing at them.

Some stories highlight Santoshi’s keen observations and his engaging ability to present concise narratives on themes beyond simply displacement from Kashmir. They delve into matters like corruption, selfishness, and the struggle for survival while incorporating elements of humor. Stories such as “Pahalwan Ki Moonchh,” “Saanp Aur Boodi Aurat,” “Jannat Ki Sair,” “Vrishabh,” and “Mitti Ki Gawahi” belong to this category.

“Eik Tha Comrade” depicts the implementation of communism within the Kashmir Valley, highlighting the scheduling conflicts between party meetings and Friday prayers. In “Hum Kahin Bhool Na Jaayein” (lest we forget), Santoshi reflects upon the aftermath of Pakistan-sponsored terrorism in the valley, which inflicted untold suffering on innocents, particularly Kashmiri Pandits. The narrative depicts how, after a campaign of hate and violence, religious minorities were forced to flee to safeguard their lives and dignity, shattering the age-old spirit of tolerance and composite culture. Each incident recounted in this chapter stems from the author’s diary, starkly illustrating the daily struggles faced by Pandits both during the harrowing period in Kashmir and their subsequent attempts to rebuild their lives in the plains.

This book transcends mere storytelling; it serves as a historical record, compiling diverse perspectives on anguish and suffering, and documenting the trials of exiles. Regardless of how one describes it, this work is essential for possession, reading, and discussion. An undercurrent of optimism permeates many stories, encouraging readers to resonate with Jalaluddin din Rumi’s lines;

‘hamchoosabzeh bar baarharoedha-em’

(Like green turf, we shall appear again and again in every spring)

Leave a Reply